Burlina, untamed queen of the plateau

Between history and legend, it is Mario Rigoni Stern who tells an amusing anecdote about the most titled of the Seven Municipalities Plateau cows

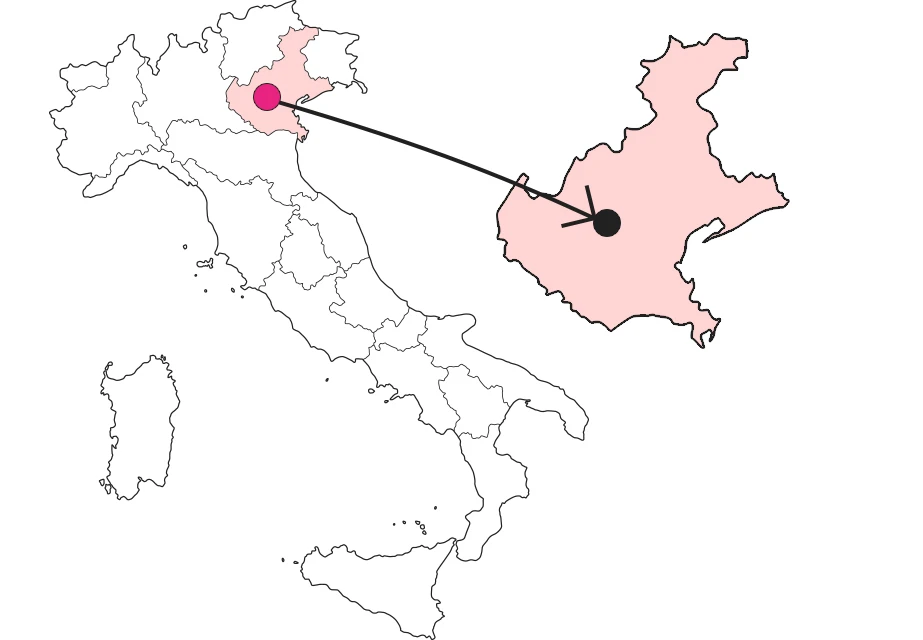

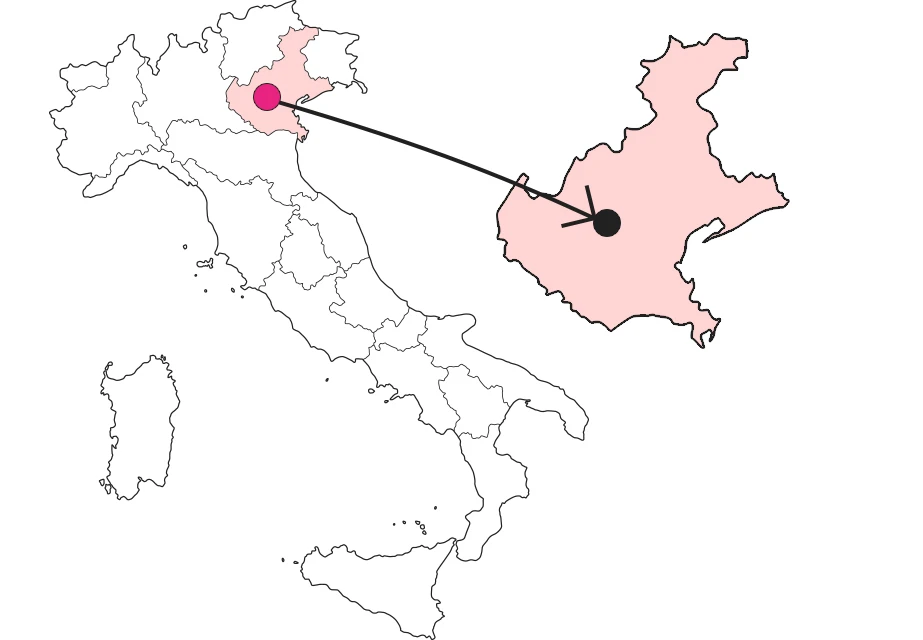

Where is

Burlina is a spotted cow, nice in name and appearance, and you can bet that sooner or later she will become the plush mascot of the Seven Municipalities Plateau. He deserves it, because he has a fictional story that unfolds over a span of more than two millennia. First reference date: the year 100 B.C.; background: the Jutland peninsula, between the North Sea and the Baltic, now part of Denmark. Here lived the people of the Cimbri, infamous in ancient chronicles for the bloody defeats inflicted on the Roman legions in their advance southward. The unfortunate people were apparently forced to dislodge because of a climatic meltdown that had made their land freezing cold. The fact is that an entire people-arms and baggage, including cows-wandered around Central Europe wreaking havoc for a decade. Then, the fatal clash with Consul Caius Marius, and here history gives way to legend, which has the few survivors ambushed in the Bavarian valleys to invent a new life as mountain people.

Highland blooms, the first factor in the exceptional nature of Asiago cheeses

Highland blooms, the first factor in the exceptional nature of Asiago cheesesThe second chapter opens with a change of scene and era, in the Vicenza of the year one thousand: a city renowned for the production of woolen "high cloths," hungry for new territories to devote to sheep farming. In those days, the plateau we now call the Sette Comuni was an almost continuous expanse of beech and fir forests, the conversion of which into pastures would have satisfied the woolen bourgeoisie. As the story goes, it was the bishop of Vicenza who had the bright idea of asking his peer in Munich to send suitable woodcutters for the enterprise, as it happens, the descendants of the ancient Cimbri, who had grown to the point where they could again be said to be a people. Thus it is that in their wake the Burlina cow also makes her entrance on the plateau. A curious name, tracing that of a mythical Danish queen, in support of this whole beautiful tale, as well as recent DNA analysis, which proves the kinship of this bovine of yesteryear with today's Friesian cattle of Northern Europe.

As soon as the milk processing is finished, the cheeses rest in wooden fascere

As soon as the milk processing is finished, the cheeses rest in wooden fascereThus we come to the third chapter, which requires another leap of almost a thousand years, to the first half of the twentieth century. The Cimbri live in dignified isolation on the plateau known as the Sette Comuni precisely because of the number of their communities: they live in thatched-roof houses, speak a distinctly German-speaking language and practice pastoralism aimed at the production of a cheese - "keeze," they say - which as early as 1931 the Touring Club's Guida Gastronomica d'Italia described as "mountain fat, made of cow's milk, known by the name of Asiago."

Burlina is their faithful companion, but a big cloud looms over the union. Mario Rigoni Stern recounts this in his novel "The Seasons of Giacomo": in fact, the year 1933, XII of the Fascist era, is running, when the order arrives to eliminate all Burlini bulls in order to favor the introduction of a Swiss breed of better aptitude, the Svitt, or the present-day Bruna Alpina. The mountain people, sensing some regime bungling, take to the streets in protest but end up in the slammer unceremoniously. Then it's the turn of their wives, who follow them to the cry of "Viva Mussolini and the Burlini bulls," and no one has the nerve to brush aside women who praise the head of the government, albeit with malice bordering on the irreverent. The event causes a great stir but does not change the fate of the Burlina cow, which within a few decades is reduced to the brink of extinction. Small and of modest production, however well adapted to the mountains, the Burlina does not hold a candle to modern breeds selected to become veritable dairy machines.

Aladino, a descendant of those Burlina bulls recalled by Rigoni Stern in one of his stories

Aladino, a descendant of those Burlina bulls recalled by Rigoni Stern in one of his storiesThe fourth and final chapter, hopefully, concerns the return of the Burlina to the pastures of the plateau and is chronicled in recent years: having recovered the few surviving herds, often of somewhat confused blood, they proceeded to bring the breed back to purity and return it to the mountains. One of the first farms to welcome it is Malga Porta Manazzo, 1738 meters above sea level, which can be a destination for a beautiful hike or drive. Here a timeless cycle of work is renewed every day: at dawn the cows are milked, before leaving them free to graze, and processing is carried out by adding this milk to that of the previous evening skimmed by surfacing; then, by sums, there is heating by wood fire in the large copper cauldron; then the small miracle of rennet, which separates the liquid and solid components; finally, the recovery of the mass to be put into shape and the salting that marks the start of the maturing process. Special studies have proven it: Asiago cheese from Burlina cows has no comparison.

Malga Porta Manazzo (m 1795), involved in the Burlina cow revitalization program

Malga Porta Manazzo (m 1795), involved in the Burlina cow revitalization programThis is the spectacle that is repeated in each of the plateau's 87 malgas "loaded" with cattle and sheep each year. These are numbers of a true dairy paradise that also for this reason deserves to enter the list of World Heritage Sites. To get to know it today, one travels the Via delle Malghe, a network of 16 tabulated itineraries serving unique nature and gastronomic tourism.

Enter the Map of Italy's Undiscovered Wonders and find treasures where you least expect it... Inspire, Recommend, Share...

The Map thanks:

Enter the Map of Italy's Undiscovered Wonders and find treasures where you least expect it... Inspire, Recommend, Share...

Where is